Sustainability Solutions: Carbon Ranching

Image courtesy Fibershed

At Bare Ranch, nestled into the eastern foot of Nevada’s Warner Mountain Range, rancher Lani Estill’s sizeable flock of sheep roam the high desert, grazing from one area to another with the rhythms of the season. Turns out, this landscape is perfect for the Rambouillet sheep. Estill sells the sheep’s supersoft wool via her own direct-to-consumer label, Lani’s Lana, as well as to yarn companies to dye and distribute separately. These pastoral details could be the end of a story about a hard-working local fiber producer—but this time, it’s just the beginning.

Estill’s wool is as versatile as all wool is: it can be woven or knit, thin or thick, made into anything from a floor-sweeping cardigan to a pair of practical socks. Like other wool, as long as it’s not combined with synthetic materials, such as polyester or nylon, it will biodegrade in the most basic of compost heaps. But if decently cared for, it can make garments that are so durable they last for generations.

But Estill’s wool is very different from other wools in one important way—its production pulls more carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere than is generated in creating it. That fact is how it gets its special name: Climate Beneficial Wool. Last year, The North Face used that wool to create its popular Cali Wool Beanie (pictured above).

What did the Nevada rancher have to do to earn this unique label? She worked on making changes to her ranch operations, guided by Fibershed, a nonprofit which “develops regional and regenerative fiber systems on behalf of independent working producers.” Fibershed does this work in a number of ways, from working directly with ranchers like Estill, to rebuilding regional manufacturing—they also do lots of public education. Plenty of farmers and ranchers are busy as it is. Convincing them to add another layer to their business can be a challenge. But like much of life, it’s all about the perspective.

“All ranching and farming is carbon farming,” said Rebecca Burgess, Fibershed’s founder. “We’re just asking them to be a conscious manager of of carbon cycling—they’ve have already been unconscious managers.” Burgess makes her case by visiting the farms and ranches and talking to their managers—often while pitching in on farm chores in a true version of the phrase “working meeting.”

Estill’s ranch now has a unique Carbon Farm Plan that takes into consideration her ranch’s environment and existing constraints. “It’s a practice-based plan,” says Burgess. “We help with the funding, implementation and planning,” she says, and then the rancher has to do the work. Part of the Carbon Farm Plan’s design allows Estill to choose which changes to make out of a list of 35 approved practices, all of which are based on known soil-improvement practices, extensive sampling and modeling, and cutting-edge agricultural science.

Image courtesy Fibershed

For example, Dr. Marcia deLonge of UC Berkeley’s Silver Lab studied the carbon inputs and outputs of sheep grazed on rangelands. Worldwide, this type of land stores 30 percent of the carbon stored in all soils. DeLonge found that even more carbon can be stored in rangeland soils that have compost spread on them. By calculating how much carbon is drawn down into those soils, and subtracting the carbon output created by the grazing sheep and the wool processing, deLonge found a net carbon benefit—more carbon was stored than released.

So what was the first thing Estill did on her ranch? “We started making compost. For the first big pile we mixed manure with woodchips from cut juniper, which is a noxious weed, and bad for [native] sage grouse,” said Estill. Compost has an advantage over just spreading manure (which is what Estill was doing before) because the heat produced by composting materials naturally kills weed seeds. At the end of the compost process, Estill has not just drawn down more carbon, she’s also gotten rid of invasives, killed weed seeds naturally, and applied even more organic matter to the soil.

Making the changes according to the Carbon Farm Plan isn’t an overnight project: “You have to tackle [these changes] slowly because agriculture is so demanding,” explains Estill. “The basics—feeding, lambing—are going to come before big projects like riparian restoration.”

But as the expression goes, slow and steady wins the race—climate change didn’t happen overnight, and neither will the solutions to it. What else is Estill doing on her ranch? “We did some water savings by changing out sprinklers to low-flow, and we were already practicing minimum tillage for our alfalfa seeds.” Implementing a shelter belt came next. “We put in 4 miles worth of trees, and a pollinator understory—shrubs and forbs and grasses that are preferred by bees, like rosehips and wild sunflower— and all of that cover helps draw down carbon into the soil. It’s also great shelter for the sheep when they’re lambing,” said Estill.

Clearly, these changes aren’t just good for pulling carbon from the atmosphere—they can also add to the beauty, value, and functionality of a ranch or farm. But they’re not cheap: The sprinkler heads Estill mentioned above are $15,000 each, the shelter belt cost $40,000, and the compost program costs $28,000 a year according to Estill. She’s able to afford to do these projects with grants from Fibershed, who are in turn getting funding from a range of sources, including retailers themselves. Like the North Face’s Backyard Project where "the focus is on going back to the fiber level to change the way our products are developed,” said Eric Raymond, spokesperson for The North Face. The outdoor retailer gave a grant to Fibershed to use at Bare Ranch (a sheep farm) in order to implement their Carbon Farm Plan in 2014. In 2016, they began production of the Cali Wool beanie made with Estill’s Rambouillet wool from the program.

But it paid off: “While a new concept, the Cali Wool Beanie was our No. 1 selling beanie on The North Face online store when it launched last fall,” said Raymond. The company is expanding the idea —a jacket, and other accessories from Estill’s Climate Beneficial wool are coming soon for their Fall 2018 collection. “Consumers care more about where their products are coming from and the impact they’re having on the earth,” said Raymond.

Well, some consumers, anyway. The reason you can buy fast-fashion t-shirts for $3.99 or distressed skinny jeans for $15.99 is, after all, glossed-over theft: To make and distribute clothing at prices that are less expensive than anyone has paid through human history, the people who make those clothes are underpaid and sometimes literally enslaved. A second theft occurs when clean water, air—and therefore community health—is negatively affected for decades by toxic clothing manufacturing. And then there’s all the flying and transportation as typically fabric is woven in one country, flown to another where it’s dyed, then crossed borders again for sewing or finishing. Take into consideration the carbon dioxide generated and resulting climate change exacerbated by the fashion industry from transit—this is a third theft.

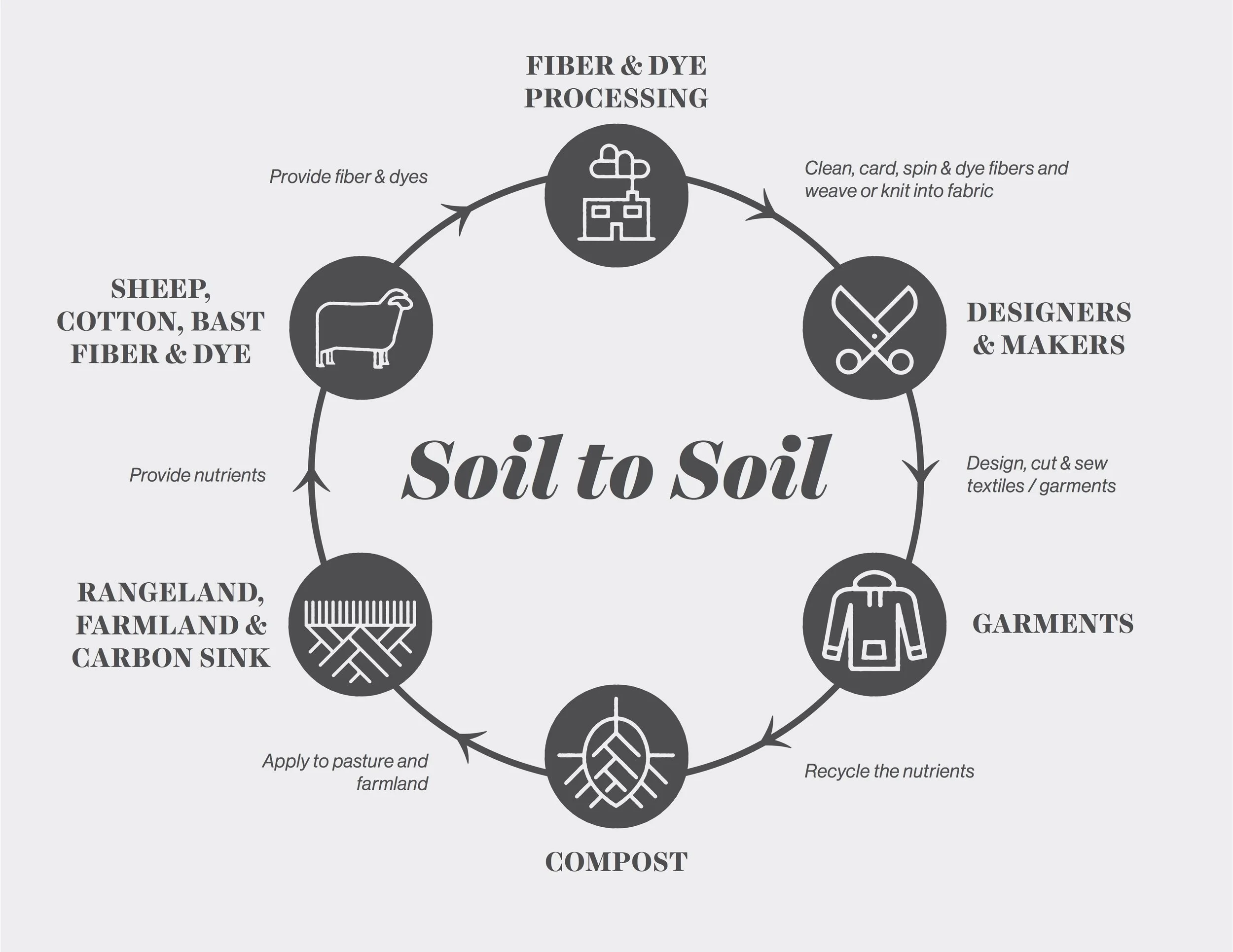

When we make something cheaper today at the expense of future people and the environment in which they live, that’s stealing from those people of the future so we can have what we want today. In Fibershed’s reality, those old, exploitative ways of creating stuff now have a positive replacement: As stated on Fibershed’s website: “Together, we can build collaborations between farmers, ranchers, land-managers, makers, and end-users to move carbon out of our atmosphere, and into our soils — while building our local economies, and generating heirloom quality and place based durable goods and textiles.”

Image courtesy Fibershed

That’s the point of all this carbon ranching—to create what we need, in a system that actually gives back more than it takes from our shared environment. Existing models show it’s possible, but now we need to scale up. Models from the Carbon Cycle Institute show that if every farm and ranch had a Carbon Plan, it could make a serious dent in our carbon problem.

Estill said her reasons for doing the work she does is two-fold: “There’s personal satisfaction in doing this—as well as doing well for the land.”

Starre Vartan is an environmental and science writer who has been published in Audubon Magazine, Slate, Newsweek, Scientific American, and others. She's now based in the Pacific Northwest in between sojourns abroad, but she'll always call New York's Hudson Valley home. A former geologist, she covers a variety of subjects in her writing, from sustainable design to astrobiology—but she still picks up rocks wherever she wanders.